The Short Version

You already have a workflow. You might not call it that. But you have one.

Maybe it starts with a brief and ends with a deliverable. Maybe it starts with raw data and ends with a board deck. Whatever the work is, there's a pattern: inputs, transformations, handoffs, feedback, revision, delivery.

You've done this hundreds of times. The creative decisions are different every time. The plumbing is not. That's not the work that needs you.

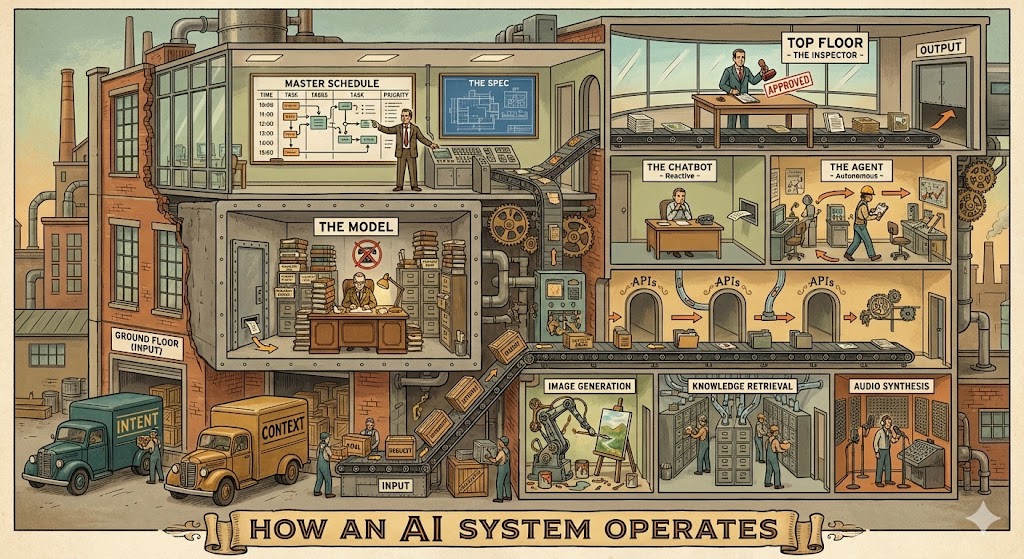

AI lets you build little factories for the mechanical parts. Input goes in. It gets transformed. Output comes out. Reliably, every time, without you babysitting it. So the creative parts get your full attention.

The first step isn't learning a new tool. It's looking at the workflow you already have and seeing it clearly. Understanding the inputs, the transformations, the handoffs, the outputs. Codifying what you already do. That's easier than it sounds, and we'll get to how.

Because once you can see your workflow as a system, you can start automating the parts that don't need you. The tools that make this possible today have names: OpenAI, Runway, ElevenLabs, Cursor. In a year, some of those names will be different. That's fine. The system you design will outlast any of them.

This guide is about how to see it. Then how to build it.

What Goes In

Every factory starts with raw materials. In AI systems, there are two:

Intent. What do you actually want? The human provides the what. Always. AI is very good at how. It is terrible at what.

- "Generate twenty variations of this hero image."

- "Produce a voiceover for this client presentation."

- "Research visual references for a rebrand."

Context. The background that shapes the output. Context is the difference between a generic output and a useful one. AI can access data. It cannot access your taste, your priorities, your read of the room.

- "The brand is minimal and warm, nothing corporate."

- "This client responds to data, lead with metrics."

- "Match the tone of the last campaign, not the brief."

These two inputs drive everything downstream. Vague intent and thin context produce vague, thin output. Every time.

The Instruction Layer

There's a specific way intent and context get delivered to an AI. Whatever you give it, text, images, audio, files, a URL, that's called a prompt. It's the input.

But there's a second layer you never see. A system prompt is a standing order on the factory floor. It's already been given to the AI before you ever type anything. It shapes the AI's behavior, sets boundaries, defines what it can and can't do.

When an AI product feels different from raw ChatGPT, that's usually a system prompt at work. If you've ever built a custom GPT, you've written one. The instructions you give it, "You are a brand strategist. Always reference the client's style guide. Never suggest stock photography," that's a system prompt. The AI follows those instructions for the entire conversation.

System prompts are one of the most powerful design levers in AI. They're not code. They're just clear writing with clear intent. If you can write a good creative brief, you can write a good system prompt.

The Model is the Engine

At the center of every AI system is a language engine.

Not language as in French or English. Language as in film language. Visual language. Musical language. A way of representing meaning. Text is one language. Images are another. Audio, video, code. These are all languages, and a modern AI engine processes all of them.

Under the hood, it's a model trained on a massive amount of data to become very good at one core task: predicting what comes next. You give it the beginning of a thought, it completes the thought.

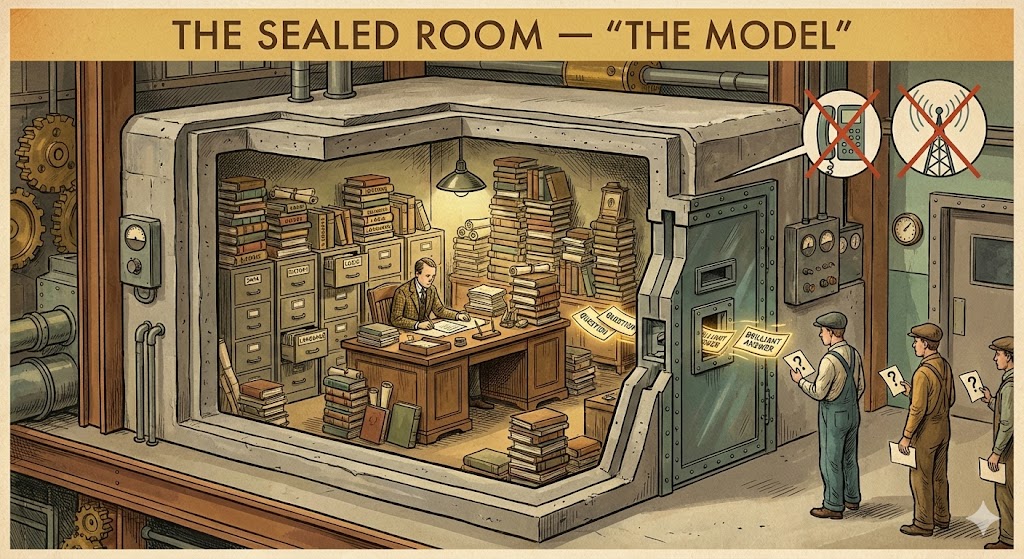

A model by itself has no screen, no memory, no internet access. It doesn't know who you are. It's a sealed room with an incredibly capable simulation of a person inside. You can slide notes under the door and get brilliant answers back. But without machinery around it, that room is all there is.

Everything that goes in and comes out gets broken into chunks called tokens. Think of them as the smallest units the model can see. A word is a token or two. An image is hundreds. Models have a fixed working memory (a "context window") that holds a limited number of tokens at once. Go past that limit and the earliest information just falls off. Every AI system is designed around this constraint.

But an engine alone doesn't produce anything. It needs workstations, workers, and a floor plan.

Tools and APIs are the Workstations

A tool is something a model can use. A web search. A file reader. A database lookup. An image generator. A video renderer. A voice synthesizer.

On its own, a model generates output. It can respond to a question, describe an image, or complete a thought. But it can't reach beyond itself. Tools extend what models can do in the real world. Pull current data. Read a document. Generate an image from a description. Convert a script into audio.

Remember the sealed room? Tools are what you put inside it. A phone. A filing cabinet. A camera. A mixing board. Each one extends what the person inside can do without changing how they think.

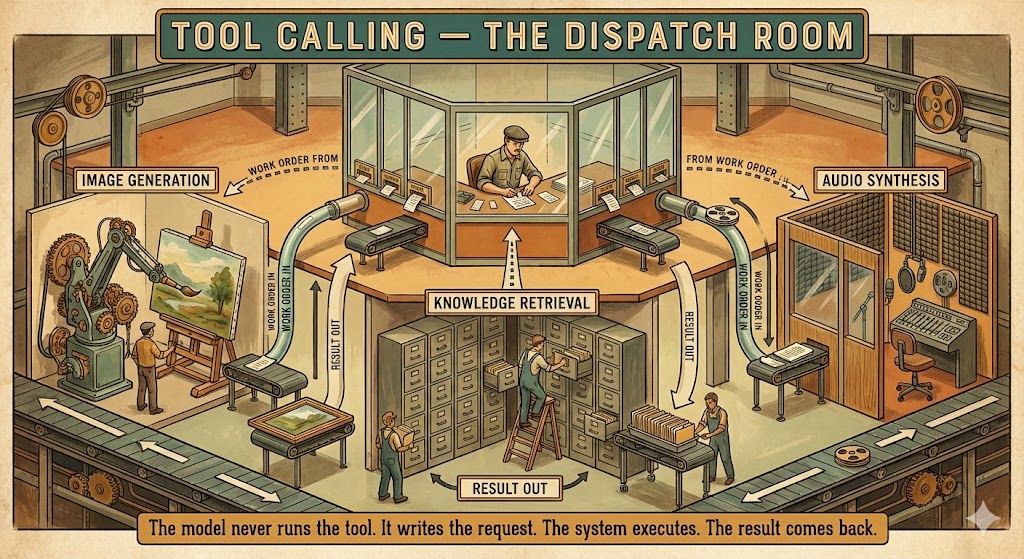

How tools actually work

When a model "calls a tool," it does something specific. Instead of generating a response, it generates a structured request: "I need to use the image generator with this description and these parameters."

The system around the model sees that request, runs the actual generation, and feeds the result back. The model then uses it in its final response.

The model never runs the tool itself. It just asks. Think of a foreman in a glass booth on the factory floor. The foreman doesn't operate the machines. The foreman writes work orders and slides them through a slot to the right workstation. The station does its thing. The result comes back on the conveyor. The foreman reads it and decides what to ask for next.

What's cool about this: a model can use tools it was never specifically trained on. You can hand it a new tool tomorrow and just describe what it does. "This tool generates video from a still image. Give it an image URL and a motion description." The model reads the description and figures out when and how to use it. How well it does this depends entirely on how clearly the tool is described.

You don't retrain the model to add new capabilities. You just put new tools on the floor.

APIs are the Doors Between Workstations

Every digital service has what's called an API. An API is a door.

Your bank has a door. Google Maps has a door. Every creative tool has a door. When you use an app, the app is knocking on doors for you. A video editing app knocks on storage doors, rendering doors, export doors. You never see the doors. You just see the timeline.

To "call" an API just means to knock on a door. Send a structured request, get a structured response back. You'll hear "API call" constantly in AI conversations. That's all it is. A knock.

Three things matter about every door:

What it expects. You can't just yell at it. You have to structure your request in a way the door understands. "Image: this URL. Style: cinematic. Duration: 4 seconds."

What it gives back. Structured information in a predictable format.

Who has the key. Most doors are locked. You need credentials. An API key is a password that says "this system is allowed to knock on this door." Some doors are free. Some cost money per knock. Some have rate limits.

When you design an AI system, a huge part of the work is deciding which doors to connect. What should the AI have access to? What can it read? What can it change? What can it create? These are design decisions, not code decisions.

The Workers: From Chatbots to Agents

Now we have an engine and workstations. Who's running them?

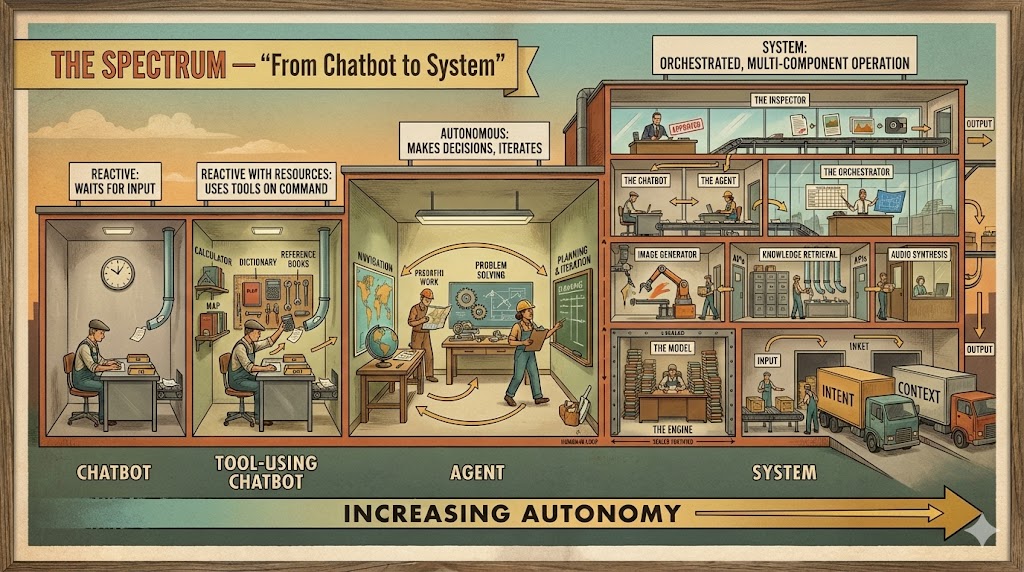

The Chatbot is the Reactive Worker

A chatbot is a model with a text box. You type, your text goes to the model, the model responds. That's it.

When ChatGPT launched, it was exactly this. Since then it's grown into something much more capable. But the core pattern is still: you ask, it answers.

If your only experience with AI is chatbots, that's like your only experience with a kitchen being the microwave. It works. It's useful. It's a fraction of what the kitchen can do.

The Agent is the Autonomous Worker

An agent is a system built around a model that can decide which tools to use, when to use them, and in what order.

This is the important distinction. A chatbot responds to you. An agent acts on your behalf.

When you tell a chatbot "I need this resized for Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn," it gives you the dimensions. When you tell an agent the same thing, it resizes the image three ways, names the files, and drops them in your export folder.

The difference is decision-making. An agent has tools and a loop: think about what to do. Pick a tool. Use it. Check the result. Think about what to do next. Keep going until the job is done.

The spectrum

These aren't hard categories. They're a spectrum:

Workflows vs. Systems

You already have a workflow. The question is whether it's codified or just habitual. Most creative workflows are habitual. You do the same steps in roughly the same order because it works, not because anyone wrote it down. That's fine for a human running the process. It's useless for automation. A machine can't run a habit. It needs a system.

A codified workflow is a fixed line

Step 1: Client uploads assets. Step 2: AI resizes for all social platforms. Step 3: Formatted files get sent to the asset library.

Written down. Explicit. Every step defined. It always runs the same way. No decisions. No branching. No adaptation. A bottling plant. Useful when the input is always the same shape.

This is where automation starts. You take the habitual workflow, make it explicit, and let a tool run it. Valuable. But rigid. If the asset is a video instead of an image, the line breaks. If the library is down, the line breaks. It can't think. It just executes.

A system is an adaptive factory

Same scenario as a system: Client provides assets. The system looks at them. Images? Resize and format. Video? Extract key frames, then resize. A mix? Sort them first, then route each type to the right station. Send to the asset library. Library down? Queue and retry. Still down? Notify the project manager.

The system makes decisions at every step. It doesn't follow a script. It follows a strategy.

This is what "agentic" means. The system has agency. It can choose. It can recover. It can route. The workers on this factory floor can think, not just execute.

Your workflow already has both kinds of work in it. The parts that are always the same (export, format, upload, notify) can be a fixed line. The parts that require judgment (what kind of asset is this? who needs it? is it good enough?) need a smart factory. The design skill is knowing which is which. And then building accordingly.

The Loops

This is the most important section in this piece.

If you take one concept from everything here, make it this one. Tools are interesting. APIs are useful. But loops are what turn a pipeline into a studio.

A pipeline without loops is a slot machine. You pull the handle and take what comes out. A pipeline with loops is a design process. You pull the handle, evaluate what came out, and decide whether to pull again, adjust, or move on.

The gap between a first draft and a final deliverable is always loops. AI systems work the same way.

The refinement loop

You give the system a first draft. You review it. "The tone is too formal." It revises. You review again. "Better, but cut the second section." Revised again. This is the loop most people encounter first, and most people stop here.

But look at what's happening: each pass through the loop, the output gets closer to what you actually want. The AI didn't get it right the first time. It rarely will. The people getting real value from AI treat the first output as raw material, not a deliverable.

The execution loop

An agent working on a task runs its own internal loop. "What's my goal? What have I done so far? What should I do next?" It acts. Checks the result. "Am I done? No? What next?" Over and over until the task is complete or it gets stuck.

This is what separates an agent from a chatbot. The agent keeps working. It tries something, evaluates the result, tries something else. It recovers from its own mistakes without you intervening.

The quality loop

Before publishing, before sending, before shipping: inspect. Did the output match the intent? Is it accurate? Is it appropriate? If not, send it back through with corrections.

You can automate this. "Check this draft against the brand guidelines. Flag anything that doesn't match." The system reviews its own work before a human ever sees it. Not a replacement for human judgment. A filter that catches the obvious problems so your review time is spent on the subtle ones.

Where the loops go is a design decision

This is where system design gets interesting.

A simple system has one loop: you review the final output. A sophisticated system has loops at every critical point. The brief gets reviewed before images are generated. The images get checked against the brief before they go to video. The video gets reviewed before the voiceover is added. Each loop catches problems earlier, when they're cheap to fix.

Think about where errors compound in your current workflow. That's where a loop belongs. If a bad brief produces bad images, which produce bad video, which wastes a voiceover generation, you've burned four API calls on something that should have been caught at step one. Put a loop after the brief. Check it before anything downstream runs.

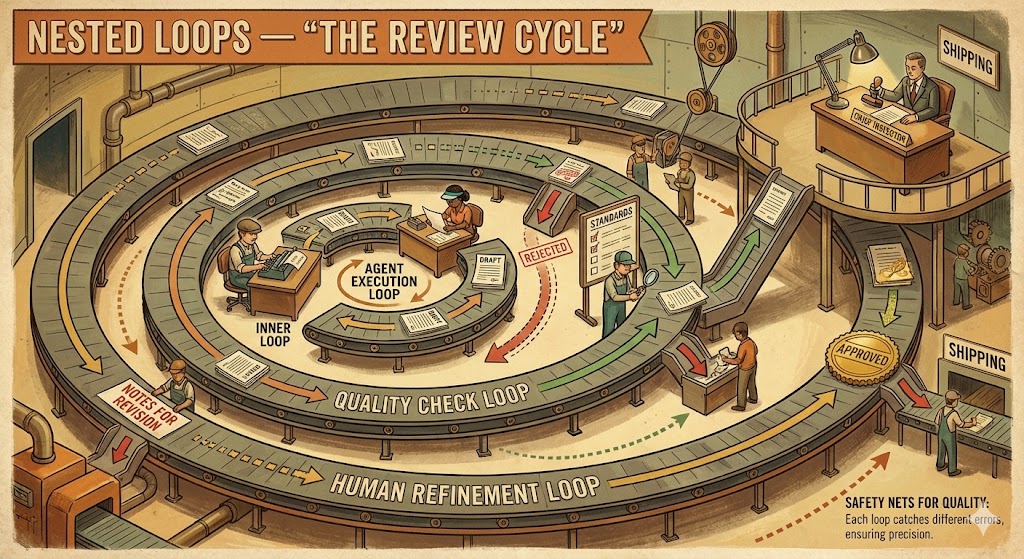

Nested loops

The most robust systems have loops inside loops. The agent loops internally on its task (execution loop). The system loops on quality checks (quality loop). The human loops on the overall output (refinement loop). Like a factory where every station has its own quality check, the floor manager does a pass, and then there's a final inspection before anything ships.

Take the video production pipeline from earlier. Inside step 2 (OpenAI analyzes the deck), the agent might loop three times to get the brief right. Inside step 4 (Runway generates video), the system might check each clip against the brief and regenerate any that miss the mark. You review the assembled rough cut at step 7 and send notes. Each layer of loops tightens the output.

Loops that learn

A loop that only repeats is useful. A loop that improves across iterations is something else entirely.

Every time you send notes back ("too corporate," "needs more energy," "wrong aspect ratio"), that feedback can be captured. Stored. Used to refine the system prompt, the default parameters, the quality checks. The tenth video your system produces should be better than the first, not because the AI got smarter, but because your loops accumulated better instructions.

One caveat: this only works when a human is providing the feedback. Left to review its own output, an AI's taste quietly narrows. The same phrasings. The same safe choices. The same three jokes. The human in the loop isn't just catching errors. They're injecting the variety and judgment that keeps the system from collapsing into repetition.

The loops don't just fix errors. They encode your taste, your standards, your judgment into the machinery itself.

When you're designing a system, the most important decisions aren't which APIs to use. They're where the loops go, who controls them, and what they learn.

The Orchestrator is the Floor Manager

Multiple tools, multiple agents, multiple steps. Someone has to coordinate. This is orchestration: which station handles what, in what order, what happens when something fails, and when the job is done. Sometimes that's you clicking through steps. Sometimes it's an AI agent coordinating other agents. Sometimes it's a workflow tool wiring services together visually. Clear goals. Flexible execution.

The Human is the Inspector

Every useful AI system has humans in it. At the beginning (you decide what to make), in the middle (you steer when it drifts), and at the end (you judge the output). AI will confidently produce wrong answers. The industry calls this hallucination: output that sounds correct but is fabricated. This isn't a bug getting fixed soon. It's how the models work. They predict plausible output.

Plausible and true are not the same thing.

The human-in-the-loop isn't a safety feature. It's the core architecture.

As Thomas Keane from the game studio Meaning Machine puts it: AI left to its own devices produces slop. That's not an indictment of the technology. It's a description of what happens when no one is checking the work. Most of what people call "AI slop" wasn't produced by bad models. It was produced without a human in the loop.

When the Line Breaks

Five ways, in order of how often they'll bite you:

- The model forgets what you said. Context overflow. The conversation got too long and the early instructions fell off.

- It makes things up. Hallucination. Confident, plausible, wrong.

- It does what you said instead of what you meant. Vague instructions, literal execution.

- It silently works around broken tools. A failed API call, a missing file. Instead of stopping, it improvises.

- It does exactly what you designed and nothing more. You said "send emails" and it sent emails. At 3 AM. To a VIP client. With an unreviewed draft.

Every one of these is a design problem, not a technology problem.

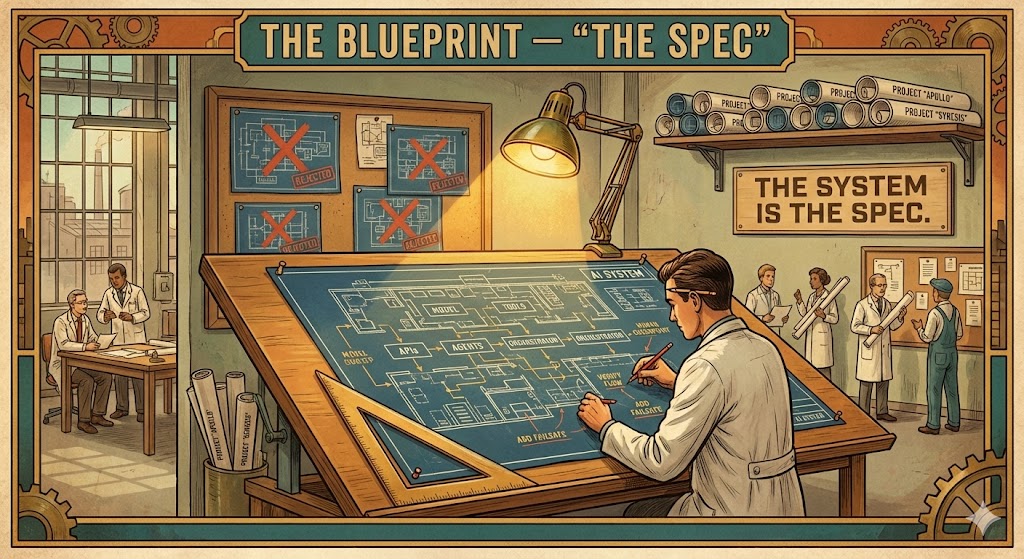

The Spec is the Blueprint

This is where we come full circle. Remember: you already have a workflow. You just haven't written it down.

The blueprint is the written-down version. In AI systems, it's called a spec. A spec is not code. It's not a prompt. It's a clear, structured description of:

- What the system should do

- What it should NOT do

- What it has access to (which tools, which data, which doors)

- How it handles failures

- Where humans are in the loop

- What "done" looks like

It's a creative brief. For a machine instead of a team.

Here's what a real one looks like. Say you produce a weekly design inspiration digest for your team:

Input: My saved bookmarks from the week + 5 design RSS feeds + Dribbble trending

Process: Scan all sources. Pull anything related to motion design, brand identity, or spatial UI. Summarize each in 2-3 sentences. Group by theme. Flag anything from a studio we've referenced before.

Output: A single document, grouped by theme, with links to originals. Under one page.

Constraints: No paywalled content. Only cite things with a direct source. Don't editorialize.

Human checkpoint: I review before it gets shared with the team.

Failure handling: If a feed is unreachable, skip it and note it at the bottom.

Or say you send a weekly client status report that takes you an hour to assemble every Friday:

Input: This week's project management updates + time tracking data + deliverables shipped

Process: Pull activity from the last 7 days. Summarize progress by workstream. Flag anything at risk. Draft three bullet points for "next week."

Output: One-page status email, ready to send. Client's tone, not ours.

Human checkpoint: I review before it goes out.

Failure handling: If the project management tool is unreachable, note it and pull from email threads instead.

Notice what's NOT in either of those: no mention of which tool runs it. No API keys. No technical implementation. That's on purpose. The spec describes the factory. The tools are just whatever you bolt onto the floor this quarter.

If "codify your workflow" sounds like a six-meeting project with post-its and a Miro board, it's not. Open ChatGPT or Claude. Say: "I need to figure out what my workflow is. Help me codify it into a document." Then just talk it through. Five minutes in, you'll have 80% of it written down. Enough to start building from.

That document becomes your spec. Refine it. Loop until it captures what you actually do. Then hand the repeatable parts to a system and let the factory run.

This is the skill. Not learning specific tools. Not prompt tricks. Seeing how you already work as a system and describing it clearly enough to automate.

Your Factory

So what does this actually look like today?

The power is in chaining. Output from one door becomes input to the next. A presentation deck goes to a language model, comes back as a structured brief. The brief goes to an image generator, comes back as visuals. The visuals go to a video generator, come back as motion. A voice synthesizer adds narration. A stitching tool assembles the final cut. Each API adds a transformation. The context and intent you set at the top carry through the entire chain.

Here are the tools that make this possible today:

OpenAI is the Swiss Army knife. GPT-4o and its successors handle text analysis, vision (it can look at images and describe what it sees), structured output (turning messy input into clean, organized data), and image generation via DALL-E. When your system needs to think, analyze, see, or generate, this is usually the engine doing the work.

ElevenLabs is the audio layer. Professional voiceovers from text, sound effects, and music generation. When your system needs a voice, a soundtrack, or ambient audio, this is the door.

Runway turns still images into video. Give it an image and a motion description, and it generates cinematic footage. When your system needs movement, this is where stills become stories.

Cursor is where you build the factory itself. It's a code editor with an AI agent built in. You open it, describe what you want in plain English ("connect to the OpenAI API, send this brief, save the response as JSON"), and the agent writes the code, runs it, fixes errors, and iterates until it works. You're directing. The agent is typing. You don't need to be a developer. You need to be clear about what you want.

ffmpeg, databases, and glue code are the machinery between the workstations. ffmpeg stitches audio and video together, converts formats, trims clips. Databases store your assets, track state, hold the structured data your system produces. These aren't glamorous. They're essential. Every factory has ductwork.

Here's a concrete example. Say you produce short social videos from client presentations. Today you do it manually: review the deck, pull the key messages, write a script, find or create visuals, record a voiceover, edit, export for three platforms. A factory for this:

- Presentation deck goes in (the raw material)

- OpenAI analyzes the deck: extracts key messages, identifies the visual assets, generates a structured brief as JSON (language engine + vision)

- The brief drives image generation: OpenAI creates visuals that match the messaging (door #1)

- Those images go to Runway with motion descriptions, come back as video clips (door #2)

- The script goes to ElevenLabs, comes back as a professional voiceover (door #3)

- ffmpeg stitches the video clips and voiceover together, formats for Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube (three outputs from one input)

- You review the rough cuts (the inspector)

- "The second clip feels slow and the voiceover doesn't match the energy of the closing slide." Those notes go back to step 4 (regenerate that clip with more motion) and step 5 (re-record the last segment with more energy). The system reruns only what changed. Five minutes later, you have a new cut. That's the loop.

Eight steps. You used to do all of them. Now you do step 1 and step 7. The factory handles the rest. And when you send it back with notes, it doesn't start over. It fixes what you flagged.

You don't have to build the whole thing at once. Start with one repeatable part of your workflow. The asset formatting you do on every project. The research synthesis at the start of every engagement. The status report that pulls from the same five sources every week. Build a little factory for it. Define the input. Define the output. Write the blueprint. Let it run.

Then build another one. In our workshop, we'll open a working factory and look inside. Four APIs chained together. A presentation deck goes in one end. Something approaching a video comes out the other, in minutes instead of days. You'll see every concept from this piece running in real code: the intent, the context, the doors, the chain, the loops, the inspector. Then you'll modify it. Change the workflow. Swap a tool. Add a step. Build your own.

Warhol didn't stop making art when he built The Factory. He made more of it. Better. Faster. And the work he couldn't systematize, the creative direction, the taste, the judgment, the intent, that got more of his attention because the mechanical parts were handled.

Monday morning. Pick one thing you do every week that follows the same steps. The status report. The asset export. The research synthesis. Pick something where you already know what good looks like. Code has diffs and tests. Reports have templates. If your workflow doesn't have a built-in way to review the result, build that first. The review infrastructure is what makes automation trustworthy.

Write down the inputs, the steps, the output. That's your first spec. Open Cursor and say "help me build this." You'll have a working prototype by lunch. A prototype, not a product. As Andrej Karpathy (who led AI development at Tesla and OpenAI) puts it, getting something to work 90% of the time is just the beginning. Getting it to 99% is the same amount of work again. And 99.9% after that. But you don't need perfection on day one. You need a working loop and a human checking the output.

That's how it starts. One workflow, written down, automated, running. Then you build the next one.

Further Reading

If you want to go deeper, these are the people and resources worth following.

People

Ethan Mollick (One Useful Thing). Wharton professor writing the most grounded, practical analysis of what AI can actually do. His Substack has nearly 400K subscribers for a reason. His book Co-Intelligence is worth reading too.

David Shapiro. AI researcher who left his corporate career to focus on autonomous agents and cognitive architecture full-time. Deep, philosophical, and building in public. GitHub has 160+ repos if you want to see how the sausage gets made.

Wes Roth. AI news and analysis on YouTube. Covers what's shipping and why it matters. Good for staying current without drowning.

AI Daily Brief. Nathaniel Whittemore's daily podcast and newsletter. Concise and substantive. Best daily briefing in the space.

Fireship. Jeff Delaney's YouTube channel. Fast, funny, irreverent tech explainers. Not AI-specific, but when he covers AI developments, he does it with more clarity and humor than anyone. 4M+ subscribers.

If you want to geek out with practitioners who are building with this stuff daily, two friends of mine write great stuff:

Matt Sinclair. Technologist, ~30 years in digital products. Publishes monthly "Irresponsible AI Reading List" and "Machine Intelligence Reading List" on Medium. Curated, opinionated, engineering-leadership perspective. Not cheerleading.

Shay Moradi. Head of Technology at Vital Auto, co-founder of OIAI.studio. 20+ years bridging emerging tech and real organizational needs. Writes on Medium about AI from a design and innovation perspective. His website is a terminal-style portfolio, which tells you everything you need to know about how he thinks.

From the Source

Building Effective Agents (Anthropic). The reference piece for understanding agentic AI architecture. Workflows vs. agents, building patterns, clear diagrams. Moderately technical but accessible.

Claude 101 (Anthropic). Free beginner course (requires a free Skilljar account). Good starting point.

Google AI Essentials. Five modules, 5-10 hours total. Zero experience required. Earns a Google certificate.

Andrej Karpathy on Dwarkesh Patel: "We're summoning ghosts, not building animals". Karpathy led AI development at Tesla and OpenAI. This interview covers what language models actually are, why this is the decade of agents (not the year), and what's still missing. Essential viewing.

Two Minute Papers. Károly Zsolnai-Fehér breaks down cutting-edge AI research papers in short, accessible videos. Great for seeing where the technology is heading without reading the papers yourself. What a time to be alive.

Brilliant: How LLMs Work. Interactive, visual, hands-on. If you want to understand the mechanics without reading papers, this is the course.

NN/g: AI + UX Collection. Nielsen Norman Group's library on AI and design. If there's one resource on this list most directly relevant to designers, it's this one.

Ready for the Workshop?

If you're joining one of our AI Systems Design workshops, you'll want to confirm you've got the foundations down. Five questions, takes two minutes.

Related

Rules vs. Tools. My companion piece on how durable rules and interchangeable tools create systems that compound over time.

Bill Moore